Unpublished Case Round Up

My weekly pick of interesting, if unpublished, cases from the California Courts of Appeal.

In California, you cannot cite or rely on unpublished judicial opinions. (Cal. Rules of Court, 8.1115.) Only published decisions carry the imprimatur of stare decisis. But Savvy judges and attorneys will often borrow legal reasoning from an unpublished opinion in drafting a motion or brief.

Unpublished decisions allow an attorney to identify unsettled areas of the law. Here are some recent opinions I found notable.

People v. Andrews E080840 Fourth District 7/12/24:

What’s a deadly weapon?

The state of the law regarding how to determine when an ordinary object becomes a “deadly weapon” is somewhat unsettled. In 2018, the California Supreme Court attempted to clarify the issue in a case called In re B.M. Andrews is a good example of how the lower courts are implementing B.M.

Start with the basics of “deadly weapon” law in California. No one would deny that certain objects are “inherently” deadly because “the ordinary use for which the object is designed establishes their deadly character. Take a dirk or a blackjack for example.

There are other objects, however, that can become deadly based on how they are used. Such objects, while not inherently deadly, become deadly in certain circumstances if they are used in a manner likely to produce death of great bodily injury. The legal question implicated in Andrews is what principles should a judge rely on when analyzing whether use of an otherwise ordinary object amounts to assault with a “deadly weapon.” (Pen. Code, § 245.)

The facts in Andrews involve the use of glass bottles and/or bricks. Victim Garrison and Defendant Andrews are at a picnic table chatting. Garrison leaves; he soon realizes he forgot his car keys on the table. But when he returns to the table, his keys are gone. He checks nearby security footage; Andrew stole his keys! Garrison chases Andrews down about a block away. Andrews is pushing a shopping cart. Andrews denies taking the keys and tells Garrison to leave him alone. Garrison persists and keeps following Andrews. Andrews “grabbed a glass beer bottles from his shopping cart, cocked back his arm, and threw them at Garrison.” Garrison manages to move out of the way; the bottles shatter on the ground.

A little bit later, Andrews reaches into his cart and grabs some bricks. he “cocks back his arm and throws three bricks at Garrison.” one of the bricks hits Garrison on his left shoulder and Bicep. Garrison says the brick didn’t hurt “too much,” but that Andrews threw the bricks “pretty hard with some strength.”

Andrews is tried and convicted of assault with a deadly weapon. (Pen. Code, § 245.) The question is whether Andrews’ use of the bottles and/or bricks constituted use of a deadly weapons under California law?

Presiding Judge McKinster concludes “yes” and I think he is probably right. Consider, first, the definition of deadly weapon under California law:

A “deadly weapon” is any object, instrument, or weapon which is used in such a manner as to be capable of producing and likely to produce, death or great bodily injury.”

Judge McKinster then distills three principles from this definition, relying on in re B.M., that trial judges should used in determining whether an object’s use renders it “deadly” under the circumstances:

First, the object alleged to be a deadly weapon must be used in a manner that is not only “capable of producing” but also “likely to produce death or great bodily injury.” (Aguilar, supra, at p. 1029.)

Second, the standard does not permit conjecture as to how the object could have been used. Rather, the determination of whether an object is a deadly weapon under 245 must rest on evidence of how the defendant actually “used” the object. (In re B.M. 2018 6 Cal.5th 28 at p. 534.) Although the California Supreme Court held “it is inappropriate to consider how the object could have been used as opposed to how it actually was used, the court made clear it is appropriate in the deadly weapon inquiry to consider what harm could have resulted from the way the object was actually used.”

Third, although it is appropriate to consider the injury that could have resulted from the way the object was used, the California Supreme Court cautioned “the extent of actual injury or lack of injury is also relevant.” (B.M., supra, 6 Cal.5th at p. 535.) Although a conviction for assault with a deadly weapon does not require evidence of actual injury or contact, “limited injury or lack of injury may suggest that the nature of the object or the way it was used was not capable of producing or likely to produce death or serious harm.” (Ibid.)

In applying these principles, Judge McKinster concludes Andrews is out of luck. Consider the evidence. Andrews “cocked his arm back” and threw two glass beer bottles at Garrison. Garrison jerked and moved away and the bottles shattered on the ground. Andrews then cocked back his arm again and threw a full brick at Garrison. True, the brick didn’t hurt Garrison “too much”; but Garrison also testified that Andrews threw the objects “pretty hard” with “some strength.”

Judge McKinster acknowledges that Garrison was not injured. This is a valid factor to consider in determining whether the brick/bottles were deadly. But, at the same time, significant injury could have resulted from the thrown objects. Had one of the bricks or bottles struck Garrison, it was likely he would have suffered serious injury.

Some readers might say “well this was an easy case.” I would dispute that. The case is a great example of a judge struggling to extract neutral legal principles from the California Supreme Court’s In re B.M. decision.

People v. Richmond G061615 Fourth District 7/11/24

Be on the lookout for improper judicial plea bargaining

As the Supreme Court reminded us several years ago, our criminal justice system “is for the most part a system of pleas, not a system of trials.” (Missouri v. Frye (2012) 566 U.S. 134, 143.) This jarring quote makes the Richmond case all the more important. Defense attorneys need to recognize improper judicial plea bargaining

In California, if you are convicted of drinking and driving you can be subject to what’s called a Watson advisement. These advisements—which the court often makes you sign in writing— warn you that driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs is dangerous to human life and that a driver so impaired may be charged with murder if someone is killed as a result. (People v. Watson (1981) 30 Cal.3d 290, 296; Veh. Code, 23593.)

The question in Richmond is whether the trial court engaged in improper judicial plea bargaining by forcing the defendant to sign a Watson advisement in order to receive the benefit of the court’s indicated sentence.

Defendant Kelly was charged with felony possession of fentanyl for sale, felony possession of methamphetamine for sale, identify theft, and possession of a payment card scanning device. (Health & Saf. Code, § 11351; Health & Saf. Code, § 11378; Pen. Code § 530.5; Pen. Code § 502.6.) Instead of fighting the charges, she pleaded guilty “to the sheet”—that is, “she pled unconditionally, admitting all charges and exposing herself to the maximum possible sentence if the court chooses to impose it.” (People v. Cuevas (2008) 44 Cal.4th 374, 381, fn. 4.)

At sentencing, the trial judge gave Kelly a choice between two sentences:

Under the first sentence, she would effectively serve five more days in jail and 20 months of mandatory supervision. Under the second, six more days in jail and 20 months of mandatory supervision. To chose the second, she had to sign a document—like a Watson advisement, but for the sale of drugs—titled “Advisement and Waiver of Rights for a Misdemeanor/Felony guilty Plea Addendum (Controlled Substances Advisement)”

Kelley chose the second sentence. On appeal, she argued the trial court exceeded its jurisdiction by requiring her to sign the Watson Advisement. She argued the court engaged in improper judicial plea bargaining.

Ultimately, the court dismissed Kelley’s case without reaching the merits. The court held Kelley failed to object to “improper judicial plea bargaining” in the trial court. You, however, aren’t going to make the same mistake! So how can you sniff out improper judicial plea bargaining? Here’s the general framework about how plea negotiations work in California.

Negotiated plea. This is a “contract between the defendant and the prosecutor to which the court consents to be bound.” (People v. Segura (2008) 44 Cal.4th 921, 931.) These are also known as “plea bargains” or “conditional pleas.” As defense attorneys, we all recognize these: our clients plead guilty in exchange for a reciprocal benefit, generally consisting of a less severe punishment than that which could result if he or she were convicted of all offenses charged.” (People v. Orin (1975) 13 Cal.3d 937, 942.) If a judge accepts a negotiated plea, he is bound to impose a sentence within the limits of that bargain. Prosecutorial consent is required.

Court plea. This is a plea “under which the defendant is not offered any promises.” (People v. Cuevas (2008) 44 Cal.4th 374, 381, fn.4) It is also called an “open plea” “unconditional plea” or “plea to the sheet.” In a court plea, either the defendant pleads unconditionally admitting all the charges and exposing himself to the maximum possible sentence if the court later chooses to impose it, or the court first gives an “indicated sentence” followed by the defendant’s plea. In contrast to plea bargains, no prosecutorial consent is required.

Improper judicial plea bargaining. There are limits on what a trial court can do during plea negotiations. The bargaining process contemplates “the adverse parties to the case—the people represented by the prosecutor one one side, the defendant represented by his counsel on the other—will reach an agreement between themselves.” The agreement, to be effective, must be approved by the trial court. The court has no authority to substitute itself as the representative of the people in the negotiation process and under the guise of “plea bargaining” to “agree” to a disposition of the case over prosecutorial objection. (People v. Clancey (2013) 56 Cal.4th 562, 570.)

So did the trial court in this case engage in improper bargaining? We will never know. Though I am skeptical of a judge who conditions an indicated sentence on a Watson advisement.

People v. Ammar A168658 First District 7/24/24

When is a probation condition impermissibly vague?

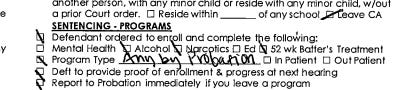

This is an important case for defense attorneys. My clients are placed on probation all the time. Their probation contains various conditions, most of which, this case taught me, are unconstitutionally vague. Let me give you a real-world example from Fresno Superior Court:

As you can see, my client was ordered under the first clause to “enroll and complete the following, alcohol, narcotics, and 52 week batterer’s intervention program,” but then under the second clause of the condition, it states “any by probation.”

Under Ammar, this clause is vague. If Fresno County Probation ever tries to violate my client I will move to strike the condition and unconstitutionally vague and violative of the separation of powers. The Fresno Superior Court has done this to a significant number of my clients. My constitutional challenge remains in my back pocket.

In this case, defendant Ammar pled no contest to stalking his former girlfriend. The trial court placed Ammar on probation subject to a number of conditions, two of which are important here:

Ammar is to “participate effectively in those programs of counseling in which they are directed to participate by the probation officer.” (Condition 6)

Ammar is to “participate effectively in any program addressing employment, education, or other rehabilitative services as directed by the probation officer and/or jail staff.” (Condition 24)

Ammar argued that both conditions are unconstitutionally vague. The lower court, Judge Goldman, agreed.

Under the separation of powers doctrine, executive or administrative officers cannot exercise or interfere with judicial authority. (In re Danielle W (1989) 207 Cal.App.3d 1227, 1235.) Courts may not delegate the exercise of their discretion to probation officers. (In re Pedro Q. (1989) 209 Cal.App.3d 1368, 1372.) By leaving key determinations to be decided ad hoc, a vague probation condition may result in an impermissible delegation of authority to the probation officer.

While a court must dictate the basis policy of a probation condition, it is permissible to allow the probation officer to specify the details. (in re Victor L. (2010) 182 Cal.App.4th 902, 919.) Where the type of treatment is specified, for example, probation officers may be given flexibility to navigate the ever-changing circumstances of court-ordered programs. However, the court’s order cannot be entirely open-ended. (People v. O’neil (2008) 165 Cal.App.4th 1351, 1359.)

In this case, condition 6 can be read to allow the probation officer to decide Whether Ammar would be required to attend any treatment. The first clause, that Ammar “participate effectively in any program…” implies that the condition is mandatory, while the second clause “are directed to participate by the probation officer” appears to mean that the probation officer could decide whether the defendant participated in treatment at all, which amounts to an impermissible delegation of judicial authority. Additionally, the condition does not specify the type of counseling required.

As for condition 24, Judge Goldman simply says “the phrase other rehabilitative services” is vague, which could result in an overbroad delegation of authority to the probation officer.

The matter is remanded to the trial court to specify the probation conditions.

Hope everyone has a good week!